In the highland homes of Saudi Arabia’s Aseer region, the walls speak. Not through words, but through vivid patterns, geometric rhythms, and colors that seem to hum with life. This is Al-Qatt Al-Asiri, a traditional interior wall decoration crafted almost entirely by women for centuries. It is a living emblem of Aseer’s identity, a practice that binds generations and turns houses into expressions of pride, hospitality, and heritage.

What is Al-Qatt Al-Asiri?

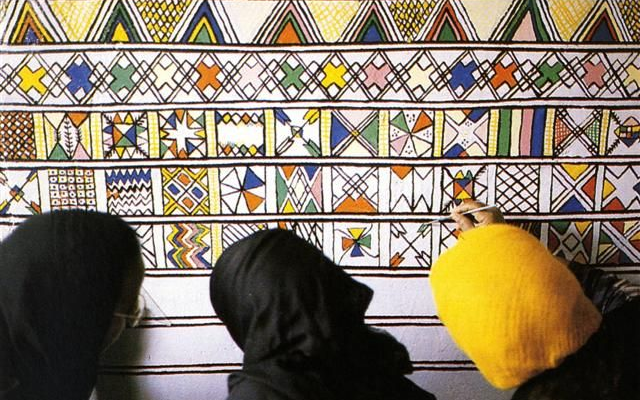

Al-Qatt Al-Asiri is an ancient decorative art form where women adorn the interior walls of their homes, especially guest reception rooms, with bold, symmetrical designs. The term “Al-Qatt” refers to the horizontal divisions that structure the wall patterns, often layered with motifs like triangles, rhombi, zigzags, and floral-inspired icons.

Traditionally, the base is coated in white gypsum or, in some areas, a pale blue wash. Onto this foundation, women paint intricate designs without prior sketching, a spontaneous and freehand expression that comes from years of observation and practice. Each shape, color, and layer has meaning, and each home reflects the personal style of the women who decorate it.

The Legend of Al-Qatt Al-Asiri's Origins

Local folklore tells of the art’s beginnings high in the mountains of Aseer. Long ago, little girls played beneath trees heavy with blossoms. Sunlight danced on the petals, casting colored reflections into their eyes. Captivated, they gathered the flowers and placed them in glasses of water. By the next day, the water had taken on the colors of the petals. The girls, enchanted, used the tinted water to paint the walls of their homes.

From that moment, the tradition grew, evolving from simple flower pigments into the rich, structured art form known today as Al-Qatt Al-Asiri.

Colors and Tools from Nature

Over a century ago, the women of Aseer drew their palette directly from the land:

- Green from crushed fresh grass.

- Red from Al Mishka, a pigmented local stone.

- Yellow from turmeric roots or the bark of the Thurb tree.

- Black from charcoal and candle soot.

- White from gypsum.

For brushes, they used goat tail hair bound into bundles. Acacia thorns became fine-point tools for dots and delicate lines. Branches were used for bold outlines. The process was resourceful and deeply connected to the environment, every mark on the wall carried the imprint of Aseer’s natural world.

Today, while synthetic paints and modern brushes have largely replaced these traditional materials, many artists still honor the old methods in workshops and heritage demonstrations.

Regional Styles and Signatures

Although Al-Qatt Al-Asiri shares a unifying style across Aseer, its expression varies beautifully from one province to another, revealing layers of regional character and pride:

- In Shahran tribal areas, the art is bold and expansive. Women favor large, open motifs painted with minimal outlines, creating a sense of airy grandeur that echoes the spacious mountain vistas.

- In Rijal Alma, the work becomes more meticulous. Patterns shrink in size but grow in intricacy. Each small shape is finely outlined in black, weaving a dense, detailed tapestry that rewards a close look.

- In Sarat Abidah, the art embraces simplicity. Fewer motifs are used, each standing on its own with clarity and presence. The result is a minimalist aesthetic where every shape breathes and commands individual attention.

These regional signatures are a testament to how artists personalize Al-Qatt within their local traditions and environments.

Also Read: Rijal Alma: The Painted Village in the Clouds

The Social Heart of Al-Qatt

Al-Qatt Al-Asiri is as much about who paints as what is painted. The process is a communal event. The lady of the house begins by sketching the main outlines and placing dots of color inside each shape. She then invites female relatives, young and old, to join her. Laughter, conversation, and shared meals fill the space as the designs take form.

This collaboration strengthens social bonds and fosters a sense of belonging. The work often intensifies before major festivals or weddings, when homes must be at their most beautiful to receive guests.

Layers of Meaning in the Patterns

Every design in Al-Qatt has a purpose. Some patterns are passed down unchanged, others adapted with personal flair. Certain motifs carry symbolic resonance:

- Triangles often represent daughters, especially when smaller triangles frame a central one.

- Geometric networks (Al-Shabaka) provide structure and flow.

- Serpentine lines (Al-Hanash) add motion and visual intrigue.

- “Khatamah” patterns reference the completion of Qur’an reading, symbolizing blessings.

The arrangement of these elements along the wall’s length creates a visual rhythm, almost like a woven textile, that guides the eye around the room.

Keeping the Tradition Alive

While historically the art was the sole domain of women, today Al-Qatt’s reach has expanded. Male and female artists, architects, and designers now incorporate its motifs into modern contexts: clothing, handbags, furniture, even corporate branding.

In Aseer, private homes have been converted into galleries to safeguard the art. Villages like Rijal Alma and cultural centers such as Al-Muftaha in Abha display Al-Qatt as part of heritage tourism. NGOs and community societies organize exhibitions, lectures, and academic research on the subject.

Fatimah Al-Almaei and her museum dedicated to preserving and showcasing Al-Qatt Al-Asiri.

Workshops are vital to preservation. Experienced practitioners, some recognized as “Al-Qattatah” masters, train girls and women of all ages. Young prodigies are emerging, blending tradition with personal innovation, ensuring that the art continues to evolve without losing its roots.

A young Saudi girl practicing the traditional art of Al-Qatt Al-Asiri.

Economic and Cultural Impact

For some artists, Al-Qatt has become a source of income. Painted canvases, decorative panels, and even souvenirs adorned with the distinctive geometric patterns are sold locally and abroad. Fashion designers have adapted motifs for textiles, making the art wearable.

This commercial adaptation has helped sustain the tradition, providing incentive for younger generations to learn and practice it, not just as heritage, but as a viable craft.

UNESCO Recognition

The 2017 UNESCO inscription was more than symbolic. It formally acknowledged Al-Qatt Al-Asiri as a vital part of Saudi Arabia’s cultural identity, highlighting:

- Its female-led tradition in a region where built heritage is otherwise male-dominated.

- Its role in strengthening social solidarity and transmitting cultural values.

- Its sustainability, thriving in homes and adapted into modern mediums.

The recognition has spurred greater national interest, leading to preservation initiatives and inclusion of Al-Qatt in cultural education programs.

UNESCO’s official video introducing Al-Qatt Al-Asiri as a recognized Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity.

A Living Canvas

Al-Qatt Al-Asiri is not a relic frozen in time. It is a living, breathing art form that continues to dance across the walls of Aseer’s homes, each brushstroke telling a story of family, identity, and place.

From its legendary origins with flower-colored water to its current status as a globally recognized heritage, Al-Qatt remains a celebration of women’s creativity. Whether in a mountain village majlis or a modern art gallery in Riyadh, its patterns still speak, of roots, of community, and of the enduring beauty of Saudi tradition.

Curious for more cultural gems like this?

Subscribe to Saudi Cultures for deep dives into traditions, regional stories, and voices from across the Kingdom.