How a desert city carved memory into rock, and kept it there for two millennia.

In Saudi Arabia, some places hold silence the way others hold sound. Hegra’s sandstone faces are quiet, but full. Doors cut into cliffs, eagles over lintels, lines of text that still speak. This was a city of arrivals: caravan leaders, stonemasons, poets, and priests. They left tombs, laws, and rituals in stone, and those stories remain.

What is Hegra?

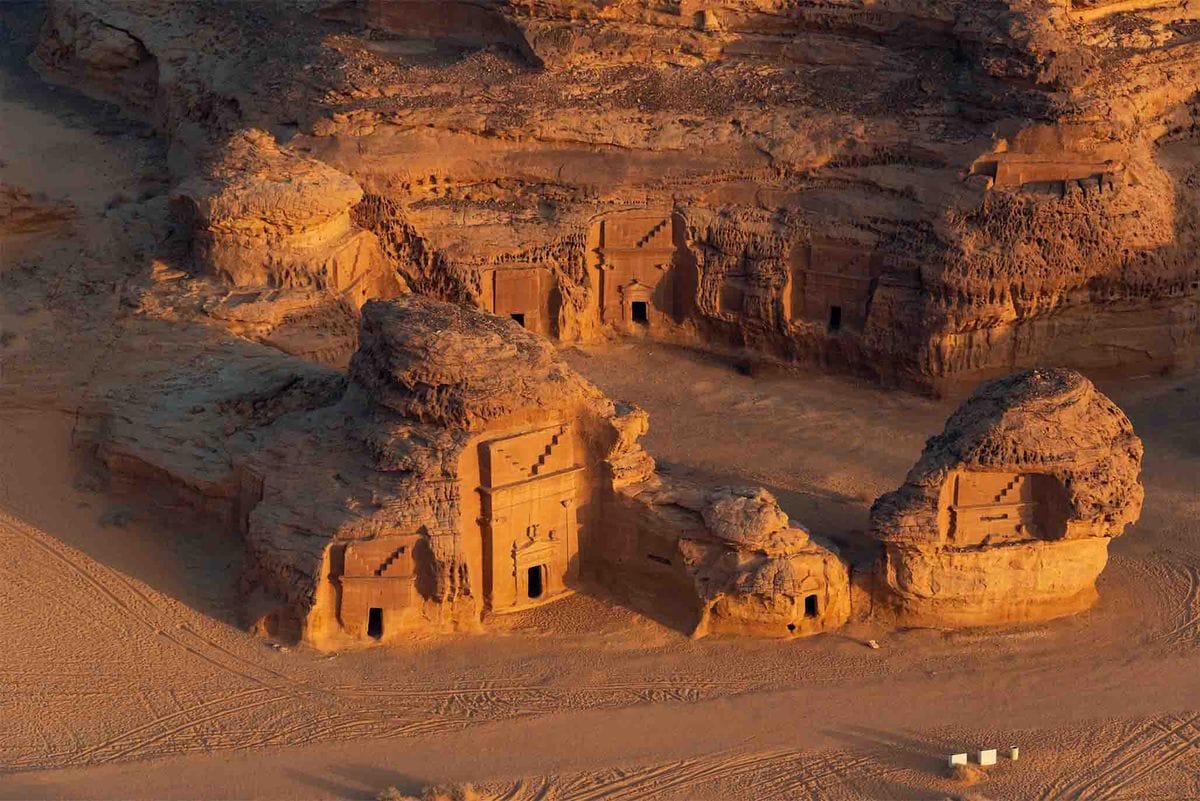

Hegra, also known historically as Al-Hijr and Mada’in Salih, is the best-preserved Nabataean city in northwest Saudi Arabia, located in AlUla Governorate of the Madinah Region. It sits where sandstone outcrops rise from an open plain. More than a hundred monumental tombs are carved directly into these cliffs, many with decorated facades from the 1st century BCE to the 1st century CE. The site became Saudi Arabia’s first UNESCO World Heritage inscription for the clarity of its architecture, inscriptions, and ingenious water systems. This is not a ruin of fragments. It is a legible city in stone.

What is the Meaning of Hegra?

Al-Hijr in Arabic means “the rocky place” or “stony tract.” Mada’in Ṣāliḥ means “the settlements of Ṣāliḥ,” reflecting Islamic memory. “Hegra” is an ancient name used in classical sources. Today, the World Heritage site is commonly called Hegra/Al-Hijr, located in AlUla.

What is Hegra Famous For?

Hegra is famous as Saudi Arabia’s first UNESCO World Heritage Site and the best-preserved Nabataean city in northwest Saudi Arabia. It contains 111 monumental tombs (94 decorated), the iconic unfinished Qasr al-Farid facades, readable Nabataean inscriptions, and ingenious desert water systems that sustained life and trade.

What is Inside Hegra?

Inside Hegra you find rock-cut tombs, clear inscriptions, and ritual spaces carved in sandstone. Tomb chambers are simple: smooth walls, benches, and loculi (small burial niches). At Jabal Ithlib, a narrow corridor leads to the Diwan hall. Across the site are betyl niches, eagle symbols, ancient wells, cisterns, and the Hejaz Railway station.

What is the Story of Hegra in Islam?

The Qur’an names Al-Hijr as the land of Thamūd and the Prophet Ṣāliḥ; the people were warned, defied the sign of the she-camel, and were punished. Prophetic reports note that Prophet Muhammad (ﷺ) passed the area on the way to Tabuk and urged humility at such ruins. The large carved tombs visible today are mainly Nabataean (1st c. BCE–1st c. CE), so Hegra holds two layers of memory: Islamic tradition and Nabataean archaeology.

From Caravan Stop to Nabataean City

Before the Nabataeans, the oasis already mattered. Traders moved incense, aromatics, and ideas along routes that linked South Arabia with the Mediterranean. Around the turn of the era, Nabataean authority consolidated here, likely during the reign of King Aretas IV, and Hegra emerged as the southern urban center of the kingdom, balancing Petra in the north. Its position drew styles as well as goods: Greek and Roman accents, Egyptian echoes, and local Arabian forms.

By the second century CE, Rome absorbed the Nabataean realm and Hegra entered a new chapter. Urban life quieted, but the facades and texts endured. The desert kept them safe.

Hegra Tombs Architecture: Facades, Symbols, and Motifs

From a distance, the tombs look like orderly portals. Up close, the design speaks its own clear grammar:

- Crow-step “stairs” crown many facades, leading the eye upward in precise steps.

- Pilasters and capitals frame the doorway with strict rhythm and balance.

- A cavetto cornice, a shallow concave band, softens the line between mass and sky.

- Eagles and betyl niches appear as protective signs, part of the funerary program.

- Additional motifs, lotus rosettes, geometric bands, and occasional feline figures, hint at a cosmopolitan craft vocabulary.

Artisans here were not copying a single model. They blended regional and Mediterranean elements into a Nabataean idiom that reads bold in sunlight and exact in shadow. Some facades rise more than ten meters. Many are so crisp that individual chisel strokes remain visible.

How Hegra’s Sandstone Was Carved

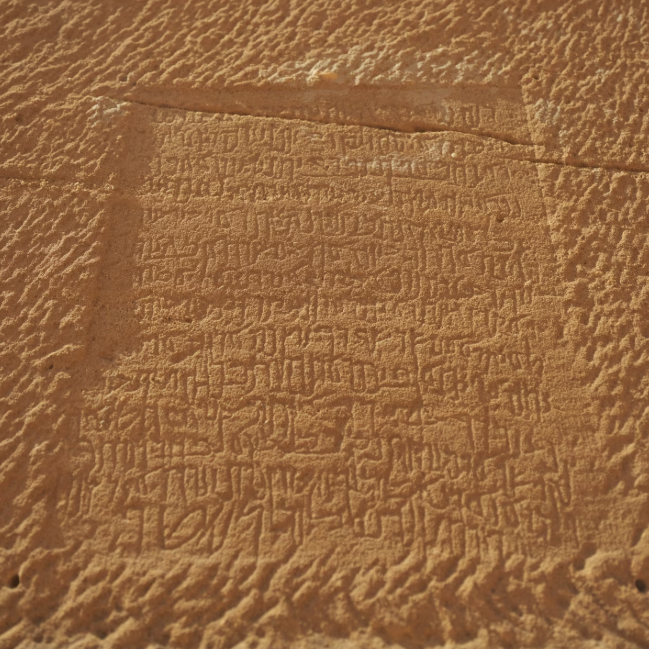

Hegra is also a textbook of technique. On several facades, the working sequence is still clear:

- Pecking: masons first “pecked” the stone to rough out a rectangular fieldespecially where an inscription would go. The surface shows a tight pattern of small hammer marks.

- Smoothing: the rectangle was then smoothed to receive letters or reliefs. Some panels remain unfinished, and the pecked texture is easy to spot.

- Setting the composition: crow-steps, pilasters, and cornices were laid out in measured bands; tool marks along edges preserve the order of cuts.

- Detailing: eagles, rosettes, and betyl niches were carved last, their edges sharpened to catch desert light.

Unfinished work functions like an open notebook. It shows how the façade grew from layout lines to full relief, evidence of a disciplined craft tradition passed from one team to another.

“Little remains of the old civil generations of El-Hejr (Hegra), the caravan city; her clay-built streets are again the blown dust in the wilderness. Their story is written for us only in the crabbed scrawlings upon many a wild crag of this sinister neighborhood, and in the engraved titles of their funeral monuments, now solitary rocks, which the fearful passenger admires, in these desolate mountains ...”

— From “Travels in Arabia Deserta” by British poet and explorer Charles Montagu Doughty widely regarded as one of the greatest of all Western travelers in Arabia, published in 1888.

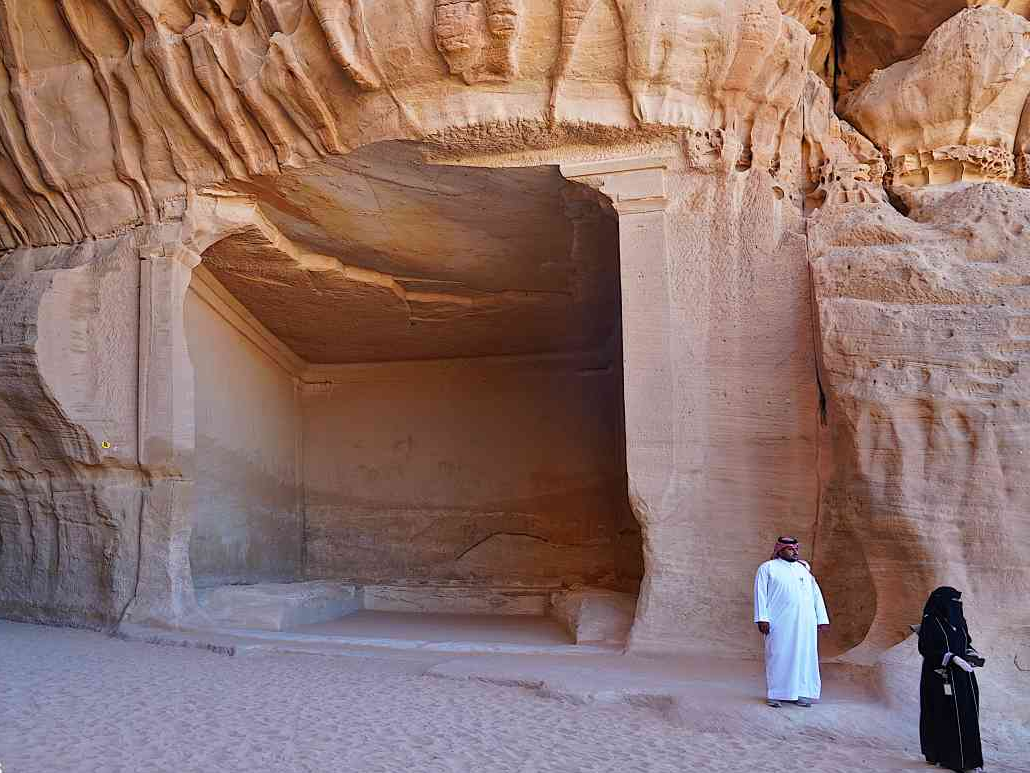

Inside the Rock: Chambers, Ritual, and Family Memory

Behind the ceremonial fronts, interiors are quiet and purposeful. Chambers are cut with small burial niches and benches; walls are smooth; ceilings can be surprisingly high. The display faces outward to the community. Memory continues within. Many tombs belonged to families or lineages, and ownership terms were carved for all to see. Some chambers include high openings that admit air and light; even these spaces keep a sober character, focused on remembrance rather than ornament.

Voices in Stone: Inscriptions, Language, and Law

Hegra’s facades often carry inscriptions: short, formal texts that name owners, record dates, and safeguard the tomb. The language is Nabataean Aramaic; the content is local and practical:

- Ownership clauses set who may be buried and who may not.

- Legal penalties (often fines) protect against trespass or reuse.

- Dates and officials anchor the tomb in civic life, linking families to authority.

- Blessings and warnings give the legal text a spiritual edge.

Look for a smoothed rectangular panel above many doorways: that is the epigraphic field. In some cases, a rough-pecked rectangle remains without text, a clear snapshot of the job mid-stream. Together, these lines let readers glimpse a legal culture that set law on the threshold, where community could read it.

Jabal Ithlib and the Diwan

In the northeast of the site, a natural outcrop known as Jabal Ithlib concentrates ritual spaces. A narrow corridor, often compared to a small siq (passage), leads to the Diwan, a rock-cut hall with stone benches on three sides. The form resembles a triclinium, a banqueting room used for formal gatherings. The place shapes movement and mood: enter through the tight passage, arrive in a cool chamber, sit together on hewn benches. Niches nearby often carry betyls, simple aniconic (does not look like a person or animal) markers of the divine. The hill, the corridor, the room, landscape and ritual fit one another.

Water and the Art of Living in a Desert

At Hegra, every beautiful façade begins with something you can’t see at first glance: water know-how. Nabataean engineers read the land, chose spots where the water table sat close, cut deep wells into bedrock, and linked them with carefully finished channels. Cisterns stored rare rainfall for months, turning a harsh plain into a livable place.

What to Look for on Site:

- Circular well openings with stone lips cut into the rock

- Shallow runnels guiding water toward storage points

- Rock-hewn cisterns near tomb clusters and paths

This quiet system powered settlement and small-scale agriculture. In a climate of heat and salt, water wasn’t a backdrop, it was the technology that made culture possible.

Qasr al-Farid: The Lonely Masterpiece

The best-known monument at Hegra is Qasr al-Farid, “the Lonely Castle.” It stands on a freestanding monolith, its façade the largest at the site. What makes it unforgettable is not only scale but process on display. The lower registers are crisp: crow-steps marching upward, pilasters set hard to the edges. Higher up, the carving stops. Chisel marks tighten, then fade, as if the team downed tools yesterday.

The result is both complete and open. It shows the city’s aesthetic, proportion, rhythm, restraint, and it shows the work that made it.

Unfinished Tomb Qasr al-Farid Stands Alone in Hegra, Alula.

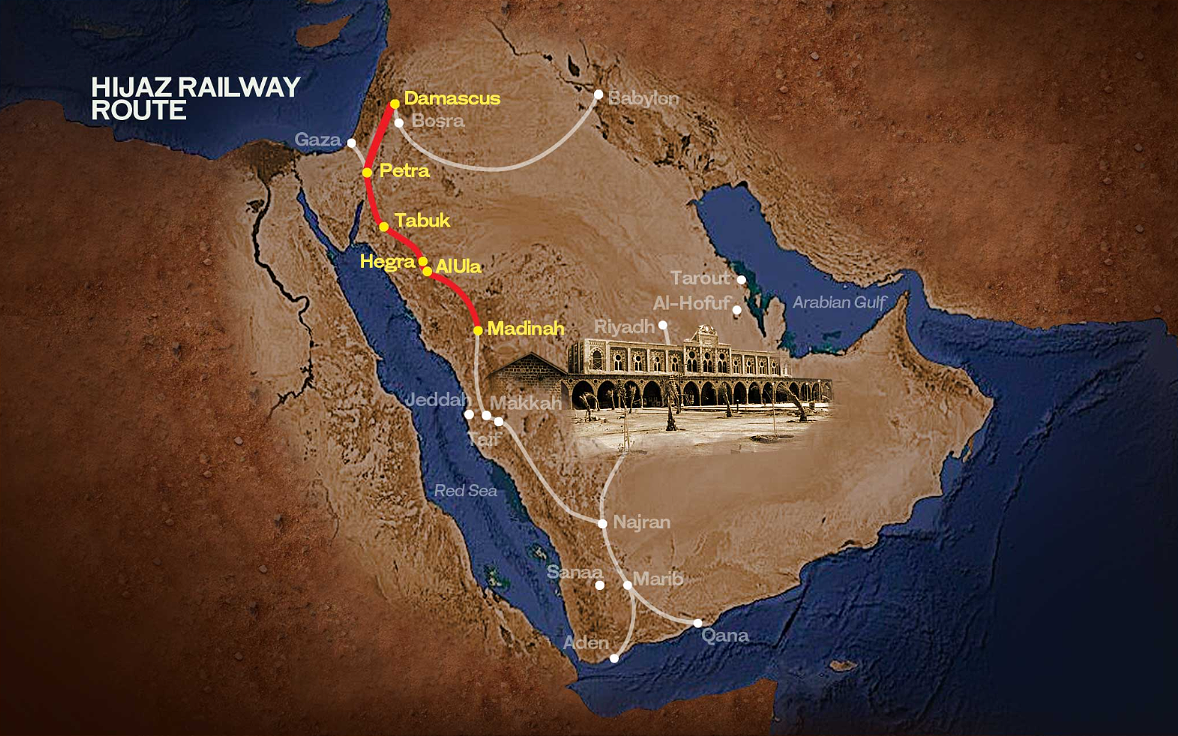

Layers of Time: The Hejaz Railway

Hegra sits within a cultural landscape that reaches into the modern era. Near the entrance, the Hejaz Railway station, built in the early 1900s as a stop for pilgrims on the Damascus-to-Madinah line, adds a recent layer to a long story of movement. The preserved buildings and locomotive shells speak of another age of travel and logistics, when steam connected the same desert to distant cities. It is a reminder that AlUla has carried travelers for centuries, by camel, by rail, and today by coach on heritage routes.

Also Read: 10 Fascinating Facts About Historic Hijaz Railway Station

How to Engage With Care (Cultural Etiquette)

Hegra is a place of memory. Treat it as such.

- Stay on marked paths and follow guide instructions.

- Do not climb facades or touch carvings; tool marks and inscriptions are fragile.

- Avoid leaving marks of any kind.

- Keep voices low. Photography is welcome where permitted; lights should be used responsibly.

- Pack out what you bring in. Respect the desert, its plants, its stones, its quiet.

Care is part of the story here. The carvings endured for two thousand years. Our behavior decides the next thousand.

Closing Reflection

Hegra teaches that endurance can be precise. Every crow-step, every bench, every line of text shows a society that turned law into landscape and ritual into rooms. The city’s beauty is not accidental. It is disciplined, learned, and local. In Saudi Arabia’s cultural story, Hegra stands as a meeting point between desert and design, memory and stone, quietly insisting that heritage is not only what survives, but what is cared for.

Curious for More Cultural Gems Like This?

Explore Saudi traditions, places, and living heritage across the Kingdom at Saudi Culture.