In the old heart of Jeddah, the buildings do something unusual. They do not hide their age. Coral stone shows through the plaster. Wooden windows lean over the street, heavy with carved detail, watching people pass below.

At the center of this memory stands Al Balad, Jeddah’s historic quarter. Built from the Red Sea, shaped by pilgrims and merchants, claimed by kings and now carefully restored, it has worn more than one face. Yet through every change, its coral houses and the watchful wooden windows have stayed in place, quietly recording Jeddah’s transformation.

Built from the Sea: Coral and Rawasheen

Al Balad is often described as “old Jeddah,” but its foundations tell a stronger story. Many of its historic houses were literally built from the sea. Their walls use coral stone blocks quarried from nearby reefs, bound with lime and mud, then washed in pale plaster. Coral stone is not just beautiful. It is practical. Thick walls help keep interiors cooler and let the building “breathe” in the coastal humidity. Light-colored finishes reflect the sun, creating natural comfort long before air-conditioning arrived.

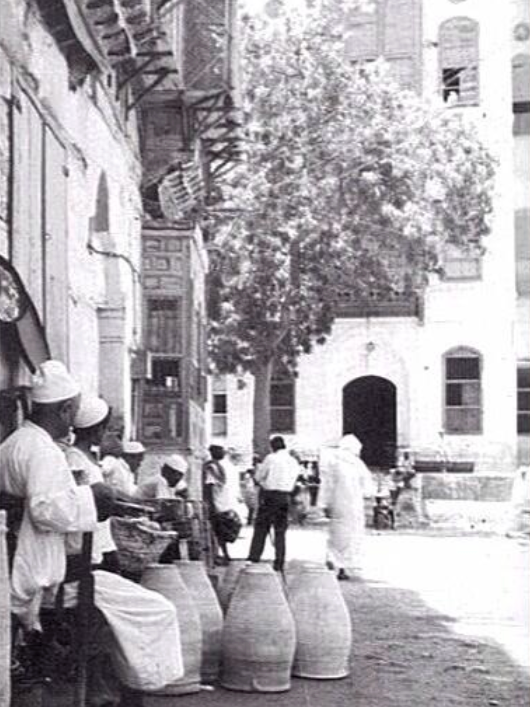

Above these walls sit the rawasheen (singular: roshan). These projecting wooden lattice windows are the most recognizable element of Al Balad’s skyline. Carved screens filter light, invite breeze, and protect privacy in the narrow streets. Many rawasheen are built from imported woods and assembled with intricate joinery, sometimes glowing with small colored glass panes.

A Historic District of 600 Coral Houses

Today, the Jeddah Historic District, which includes Al Balad, still holds hundreds of historic buildings. Many are coral-stone tower houses wrapped in rawasheen, standing shoulder-to-shoulder along lanes, markets, and small neighborhood squares. Some of these buildings are modest family homes. Others were merchant mansions linked to Red Sea trade routes and the flow of pilgrims to Makkah. Together, they form the only surviving large ensemble of this kind of urban Red Sea architecture.

Among all these structures, one house in particular feels like the storyteller of the district.

Nassif House: A Mansion with a Memory

Nassif House (Bayt Nassif) stands on Suq al-Alawi, one of the main historical streets in Al Balad. Construction began in the 1870s and finished in 1881 for Sheikh Omar Effendi Nassif, a member of an influential merchant family and governor of Jeddah at the time.

The house rises several floors above the street, with more than a hundred rooms. Inside are grand halls, staircases, storage areas, and rooftop spaces that once looked over the harbor and the dense city around it. From the outside, the façade combines coral masonry with deep rawasheen and carefully carved wooden details, showing the peak of late 19th-century Hijazi coastal design.

Just outside, in the small northern square, stands a neem tree that became famous in its own right. For decades, locals knew it as “the only tree” in old Jeddah, and Nassif House gained a popular nickname: Beit al-Shajarah, i.e. the House of the Tree.

This one building connects many of the forces that shaped Al Balad: trade, pilgrimage, governance, royal history, scholarship, and now cultural tourism. To see how, it helps to look at the three different “skins” Jeddah’s historic quarter has worn.

1) First Skin: Walled Port and Sea Gate to Makkah

Long before modern highways and airports, Jeddah already looked outward to the world. From early Islamic times, it developed as a major port on the Red Sea, linked to routes from Africa, India, and beyond. Ships brought spices, textiles, coffee, and ideas into its harbor.

Because of this position, Jeddah became the sea gate to Makkah, receiving Muslim pilgrims who arrived by ship for Hajj and Umrah. From the port, pilgrims would disembark, pass through the town, and continue inland toward the Holy City. In those days, Al Balad formed a compact, walled settlement. Gates such as Bab Makkah and Bab Medina connected the city to caravan routes. Inside the walls, mosques, markets, ribats (hostels for travelers and pilgrims), and coral homes were tightly woven into a walkable fabric. The sound of trade overlapped with the call to prayer and the constant movement of travelers.

Nassif House in the Age of Sail and Steam

Nassif House came at the height of this maritime era. The late 19th century saw intense activity along the Red Sea, especially after the opening of the Suez Canal and the growth of steamship travel. Merchant families like the Nassifs benefitted from this boom. Placed directly on Suq al-Alawi, the main commercial spine, Bayt Nassif was more than a family home. It was a public statement of status and a vantage point over the life of the city. From its rawasheen, the family could watch pilgrims and traders moving through the market, and track the rhythm of ships arriving along the coast.

2) Second Skin: Merchant Quarter in Transition

The 20th century brought a different kind of change. With the rise of the modern Saudi state and the oil era, Jeddah began to expand. New districts grew to the north. Roads, cars, and concrete reshaped how people lived and moved. The old city walls were removed. Parts of the coastline were reclaimed. Modern buildings appeared along new streets. Some long-established families left Al Balad for newer neighborhoods, seeking more space and contemporary comforts.

As attention shifted elsewhere, many coral houses suffered from a lack of maintenance. Time, humidity, and salt are unforgiving enemies. By the late 20th century, parts of the historic district were in serious disrepair, even as historians and architects started to raise alarms about the loss of a unique heritage.

A King in a Merchant’s House

Nassif House again mirrors the moment. In the early 20th century, it was known as a social and political meeting place. Consuls, merchants, and local leaders gathered within its walls. When King Abdulaziz Al Saud entered Jeddah in 1925 during the unification of the Kingdom, he stayed in Nassif House and used it as his residence for a period. A merchant family mansion became, briefly, a royal home. It is said that one of the first trees planted in Jeddah by King Abdulaziz was that very neem tree in front of the house.

Later, the house became a space of learning. It housed a private library and served as a hub for scholars, preserving thousands of books within its coral walls. Even as the surrounding district struggled, the building kept its role as a keeper of memory.

3) Third Skin: UNESCO Quarter and Living Heritage Hub

The latest chapter in Al Balad’s story begins with recognition and renewal. In 2014, “Historic Jeddah, the Gate to Makkah” was inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List. This celebrated not only the architecture, but also the district’s role as a major Red Sea port and gateway for pilgrims over many centuries. The inscription helped unlock larger preservation efforts. Under Saudi Vision 2030, the Jeddah Historic District Program now leads an ambitious plan to revive Al Balad. The focus is not only on saving individual buildings but on bringing back the entire urban fabric as a living neighborhood.

Hundreds of historic structures are being surveyed, stabilized, and restored. Many are earmarked for adaptive reuse: a heritage hotel, a gallery, a café, a cultural center, or a residential space. The idea is simple and powerful: a building has the best chance of survival when it is actively used and loved.

Nassif House Today: Museum, Landmark, and Symbol

Nassif House sits at the heart of this revival. Carefully restored, it now serves as a museum and cultural center. Visitors climb its broad staircase, stand on its terraces, and look out across streets that once saw caravans and are now welcoming tourists, residents, and artists.

Exhibitions and educational programs bring Hijazi history, architecture, and daily life into focus. Cultural events animate the square under the neem tree. The same building that once hosted a merchant governor and a founding king now hosts school groups, researchers, and curious travelers. Other coral houses around it are joining this new life. Several have already become heritage hotels and hospitality venues, allowing guests to sleep within coral walls and under wooden ceilings while still enjoying modern comfort.

The Heart of Jeddah

Al Balad’s lanes may be narrow, but its story spans centuries of pilgrims arriving by sea, merchants shaping the city’s economy, and leaders guiding a new nation. Its coral blocks, rawasheen, and shaded courtyards are a record of how Jeddah learned to live with its coast, its climate, and its role as the gateway to Makkah. Today, as Saudi Arabia restores and reinvents these historic spaces, buildings like Nassif House continue to show how the district bridges generations, keeping Al Balad’s layered past alive in the light that falls through its wooden screens.

As long as light filters through its wooden screens onto coral stone floors, Al Balad’s three skins remain part of one living story of Jeddah.

Curious for More Cultural Gems Like This?

Subscribe to Saudi Cultures for deep dives into traditions, regional stories, and voices from across the Kingdom.