In Saudi Arabia, scent is part of welcome. Long before glass vials and designer labels, two desert resins "frankincense" and "myrrh", traveled by camel and dhow, perfuming palaces, temples, and everyday majlis. This trade linked the Arabian Peninsula to faraway ports and caravan towns. Trace its route and the story is clear: sap from hardy trees growing on rock helped build roads, fill city cisterns, and shape carved stone façades.

Today’s bakhoor, perfuméd woodchips often blended with frankincense, is the home version of a very old habit: burning desert resins for welcome. It’s living proof that the Incense Route never fully ended; it endures in homes across Saudi Arabia.

The Trees Behind the Famous Scent

Frankincense is the aromatic resin of Boswellia trees, most famously Boswellia sacra. Myrrh comes from Commiphora species, especially Commiphora myrrha. Both belong to the Burseraceae family and survive where few plants would: limestone cliffs, dry wadis, and thin, stony soils. Their heartlands stretch across southern Arabia (Dhofar in Oman and eastern Yemen) and the Horn of Africa.

Because the land is harsh, the resin is rich. That is why the scent is so special, and why traders carried it across deserts for centuries.

How a Tree Becomes Incense

Harvesters make small, careful cuts in the bark. Clear sap beads into “tears” and hardens in the sun. After a few weeks, they return to collect, clean, and sort the tears by size, color, and clarity.

- Frankincense: lighter, more translucent tears are usually top grade, bright and citrusy.

- Myrrh: ranges from pale amber to deep red-brown; a rare, naturally oozing type called stacte has been prized since ancient times.

Every step is done by hand. Quality control starts at the tree.

Harvesters collecting frankincense resin by hand from Boswellia trees, using traditional tools and woven baskets to gather hardened sap.

The First Markets for Incense

The story starts with ritual power. In ancient Egypt, incense was burned in temples, used in embalming, and offered to deities. In Mesopotamia, resins filled shrines and ziggurats as part of daily worship. Levantine societiesused incense in sacred rites; frankincense is even named in the Bible as a temple ingredient. In pre-Islamic Arabia, aromatic resins played a role in ancestor worship and tribal ceremonies. Across faiths and frontiers, the sacred scent of incense created one of the world’s earliest and most enduring cultural markets.

Ancient Egyptian depictions of incense rituals: on the left, a pharaoh offering burning incense; on the right, a carved limestone scene showing a figure tending incense on an altar.

The Incense Route

The incense trade ran for many centuries and peaked from the 3rd century BCE to the 2nd century CE. The most valuable goods were frankincense and myrrh, and Saudi Arabia was the crucial corridor that carried these resins to major markets.

The Saudi Corridors (Najran as the Hinge)

Resin moved inland to the Kingdom’s southern frontier. The oasis of Najran (Al-Ukhdood) acted as the hinge where caravans chose one of two paths:

- Branch A — Hijaz spine to the Mediterranean

From Najran, caravans moved through the Asir and Hijaz oases to Hegra (Al-Hijr) in AlUla, then north to Petra and down to Gaza. This western line is the best-known part of the Incense Route because many buildings, wells, and road traces still survive.

- Branch B — Inner-desert to the Gulf and Mesopotamia

From Najran/Bir Ḥimā, caravans went to Qaryat al-Faw (a Kindah capital), then to Thaj and Gerrha on the Gulf, and onward by river routes into Mesopotamia (modern-day Iraq). This path shows the network was braided, not a single straight road.

Aerial view of Qaryat al-Faw ruins and nearby cliffs, showing the former Kindah capital’s role as a key stop on the incense trade route in central Arabia.

Route Towns & Hubs in Today’s Saudi Arabia

Towns grew rich by taxing caravans and selling water, fodder, and storage:

- AlUla: A major cultural and commercial center linked to the Nabataeans and other ancient kingdoms.

- Tayma: A powerful northwest oasis with evidence of long-distance trade over many centuries.

- Al-Abla (Asir): An ancient site with finds pointing to residential and industrial activity tied to caravan traffic.

Expensive for a Reason: Costs that Added Value

At times people even said frankincense and myrrh were “worth more than gold”. Not by weight, but because ritual demand was constant and supply was risky. After harvest and grading, traders moved the resin carefully: guides, guards, tolls, fodder, each stage added costs. Reliability mattered more than speed.

Clean, dry resin earned the highest price, and the fees paid along the way helped fund wells, walls, and markets in towns on the route.

Remains of a palace, a well, and a residential area at Qaryat al-Faw, showing how incense trade supported urban development along the route.

Cultural and Religious Integration

Spiritual Use of Incense Before Islam

In ancient Arabia, incense was part of everyday belief and ceremony. People used aromatic resins and oils in pre-Islamic rituals, to embalm the dead, and to scent sacred spaces. Many believed the rising smoke carried prayers to the heavens.

Fragrance in Islamic Tradition

With the rise of Islam, using pleasant fragrances remained important. The Prophet Muhammad (PBUH) is reported to have appreciated good scents, which helped fix fragrance as a valued part of daily life and good manners in Muslim societies.

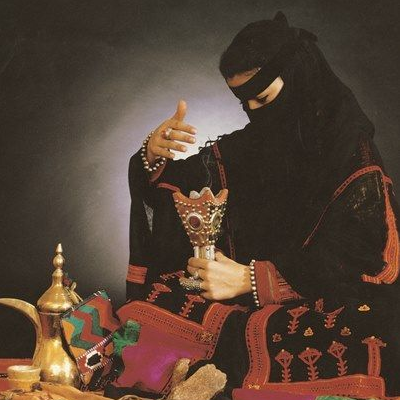

Hospitality and Status at Home: Bakhoor and the Mabkhara

In Saudi homes, bakhoor chips soaked in fragrant oils, often blended with other aromatics such as frankincense signals respect and care for guests. Families scent homes for visitors and during special occasions like weddings and feasts. The mabkhara (incense burner) is passed among guests as a polite gesture. Historically, the quality and intensity of the incense showed the host’s generosity and social standing.

Shift in Trade and Lasting Legacy

After the 2nd century CE, the incense trade changed. Maritime routes on the Red Sea expanded, and Roman demand shifted, reducing the importance of long desert caravans in some areas.

Changing Ritual Profiles

The spread of Christianity and Islam also changed public rituals. Some older practices that used large amounts of incense became less common, which affected demand, though fragrance remained part of personal and social life.

Competition from Maritime Trade

From the 1st-3rd centuries CE, Red Sea and Indian Ocean routes grew fast. Seasonal monsoon winds made sailings more predictable, and ships could carry more cargo at lower cost than long desert caravans. As ports and customs houses expanded, some overland legs lost importance. The incense trade did not vanish on land, but sea links took a larger share.

The sea brought speed; the desert kept reach. Together, they carried frankincense and myrrh farther than either route could alone, and their shared rhythm is the real story behind Arabia’s incense economy.

Ancient Monopoly Ended, But the Culture of Scent Did Not

Even as sea routes rose and caravan paths shifted, the deeper custom endured: welcoming with fragrance. What began with desert resins like frankincense and myrrh now lives on in the form of bakhoor. In Saudi homes, hosts may pass a mabkhara (censer), allowing guests to warm their hands over the smoke and lightly scent their clothes or hair. This fragrant gesture appears at weddings, after meals, and during visits. It is hospitality made tangible.

Today, bakhoor, perfumed woodchips or pressed blends often made from agarwood (oud) and mixed with oils and resins, is the modern echo of an ancient habit. Burned on charcoal, it fills homes with warmth and memory. The richness of its scent still signals care, generosity, and the timeless art of welcoming well.

Where to See the Story in Saudi Today

- Hegra (Al-Hijr), AlUla: Rock-cut tombs, inscriptions, and water systems bring the trade to life. Visit early or late for the best light and stick to marked paths.

- Najran (Al-Ukhdood): Fortified walls and inscriptions recall the southern hinge of the network.

- Qaryat al-Faw: A strategic desert town at a Tuwayq pass, rich in inscriptions and architecture tied to caravan life.

- Historic Jeddah (Al-Balad): Coral-stone houses and rawasheen speak to maritime wealth that braided with inland exchange, an urban echo of ancient trade.

From Trade Route to a Timeless Ritual

Bakhoor is more than scent. It’s a cultural inheritance that speaks without words. In Saudi Arabia, its rising smoke links generations, sanctifies spaces, and extends warmth to every guest who walks through the door. Whether used in daily rituals or grand celebrations, bakhoor remains a quiet yet powerful symbol of identity, memory, and belonging. In every curl of fragrant smoke, Saudi culture lives on.

Curious for More Cultural Gems Like This?

Explore Saudi traditions, places, and living heritage across the Kingdom at Saudi Culture.