In Saudi Arabia, some places speak in carved lines. South of Najrān, between basalt ridges and sunlit wadis, the Ḥimā Cultural Area preserves thousands of petroglyphs and inscriptions that read like a travelogue across millennia. Hunters, caravans, soldiers, and pilgrims left their marks here. Together, these marks form a living archive of people in motion, meeting where water, routes, and memory converged.

What is the Hima Cultural Area in Saudi Arabia?

Ḥimā is a vast cultural landscape in the Najrān region of southwestern Saudi Arabia. It is best known for its dense concentrations of rock art and inscriptions around the historic watering points of Bir Ḥimā. For centuries, the area lay along desert routes that linked Yemen, Najrān, and the central highlands. Travelers paused at wells, rested their animals, and left short texts or images on nearby rock faces. Because of this continuity, many call Ḥimā Arabia’s open‑air library, a place where everyday people wrote their presence into stone.

Did You Know?

The word bir means “well” in Arabic. Many of Ḥimā’s most important panels sit within walking distance of ancient wells.

Geography & Context

The landscape around Ḥimā is simple but striking. Black volcanic hills rise from pale gravel plains, and cliffs glow under the evening sun. Seasonal valleys (wadis) cut through the land, carrying rare but important water after rains. In this dry environment, wells and water holes became natural meeting points. Herders, hunters, traders, and patrols stopped here to drink and rest. While waiting, many people carved into the rocks around them.

The result is a chain of rock panels spread across the desert. Some stand alone on ridge faces, while others cluster like pages in a book. By looking at the landscape, you can understand the art. Open plains often show animal scenes, while shaded cliffs carry denser carvings of names, prayers, and stories. Geography guided movement, and that movement shaped memory.

“Open‑Air Library”: Rock Art & Inscriptions

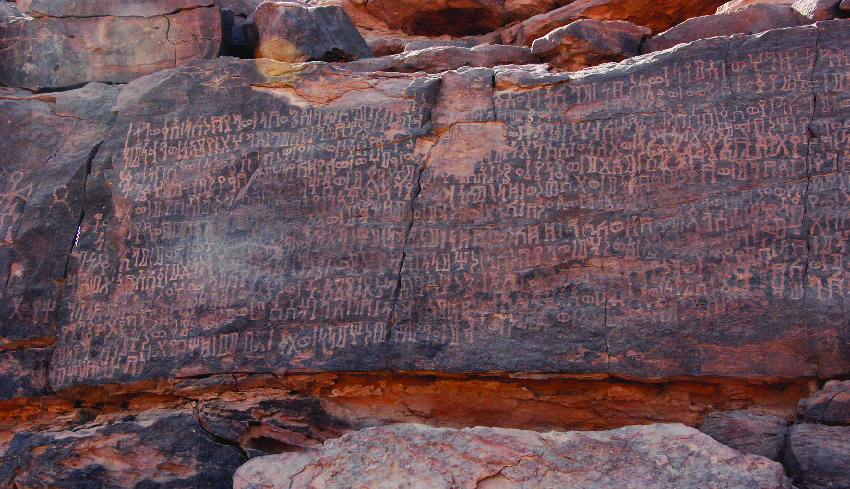

Ḥimā’s panels combine images and short texts in remarkable variety. Artists pecked figures into dark rock varnish with controlled blows, or incised them with sharp tools. Over time, the same surfaces were reused, so older, darker motifs sit beneath brighter, newer lines. A single panel can hold generations of conversations: a camel train marching under an earlier ostrich; a spear crossing the neck of a much older bull; a brief prayer tucked beside a warrior’s horse.

This mix of picture and word is what makes Ḥimā feel like a library. The images provide context, what people valued, feared, hunted, or celebrated. The inscriptions add names, languages, and dates in the broad sense. None of it is staged for a museum. It remains where it was made, in dialogue with the wells and the routes.

Time Span & Continuity

Carvings and inscriptions at Ḥimā span thousands of years. The earliest layers include hunting scenes and large fauna, while later layers introduce cavalry, prayers, and early Arabic names. This long arc means Ḥimā does not represent a single era or style. It is a stack of eras, formed by repeated visits to the same life‑giving places.

Continuity is visible in small habits: caravanners carving a name and a blessing before pushing north; soldiers sketching a line of lances after patrol; shepherds adding an ibex to a ledge already filled with ostriches. The library did not close. Each generation added a chapter.

Scripts & Languages

One of the most fascinating aspects is the diversity of the writing systems preserved:

- Musnad / Old South Arabian

- South-Arabian

- Thamudic

- Aramaic / Nabataean (Aramaic‑Nabatean forms)

- Greek

- Arabic (including early Islamic inscriptions)

This diversity shows how Ḥimā was a crossroads not just physically, but linguistically and culturally. The rock-carved narratives often combine images (figures, animals, boats, weapons) with inscriptions that may name individuals, events, or blessings.

A particularly important subset are the Ḥimā Paleo-Arabic inscriptions, a cluster of 25 inscriptions in early Arabic script discovered in the region. Before their discovery, such Paleo-Arabic script had been less well represented in the Arabian Peninsula.

These inscriptions broaden our understanding of how the Arabic script evolved and how Arabic as a written medium spread.

Themes & Imagery

The visual motifs etched into the rocks are rich and varied:

- Animals & Fauna: camels, cattle, giraffes, ostriches, desert wildlife

- Humans: hunters, riders, people in procession, dancing figures

- Scenes: hunting, battle, tribal or social gatherings

- Symbols & Signatures: some carvings are “wusum” (signatures or marks of authors or tribes), over a thousand such markers have been identified in the German-language literature on Ḥimā.

These elements reflect not just aesthetic or spiritual expression, but evolving environments, changes in fauna, human adaptation, trade, and movement through time.

The Famous Inscription Ja 1028

Among Ḥimā’s most discussed texts is an inscription labeled Ja 1028, carved in South Arabian script and dated to the early sixth century CE. It refers to a campaign that shook the Christian community of Najrān. The language is concise, yet it carries the weight of politics, religion, and conflict in late antiquity. Nearby, small crosses and personal names appear, as if private devotion gathered around public history.

For readers today, Ja 1028 transforms the site from a gallery into a witness. It is not only art; it is testimony. The stone speaks of power and suffering, recorded at the very crossroads where news would have traveled.

Spotlight

Ja 1028 is compelling because it links a local rock face to a regional event. Few desert inscriptions deliver such a direct connection between text and place.

Historical & Cultural Significance

Ḥimā reframes how we think about the Arabian Peninsula. Far from empty, this desert corridor pulsed with mobility of goods, news, and ideas. It shows how water shaped social life, how routes braided communities together, and how writing took root in everyday practice. It threads local histories of Najrān and the south into a wider national narrative. For global readers, it challenges clichés: here is evidence of continuity, exchange, and creativity across deep time.

Three lessons stand out:

- Movement is memory. When paths converge, people leave records on stone.

- Water is culture. Wells do more than quench thirst; they gather stories, prayers, and decisions.

- Scripts are journeys. From South Arabian letters to early Arabic, Ḥimā maps the moment language steps from speech into stone.

The Secrets Underneath: Wells & Water Channels

The name Bir Ḥimā, the well of Ḥimā, captures the site’s heartbeat. Deep stone‑lined shafts and shallow channels made life possible here. In a dry climate, reliable water points directed movement like magnets. This is why the densest clusters of carvings sit near wells. Caravanners paused to water herds, repair tack, and plan the next leg. Soldiers rested patrol animals and sharpened weapons. Families camped seasonally, following pasture.

Because life concentrated at water, memory concentrated there, too. Artists did not travel to Ḥimā to carve; they carved because they were at Ḥimā waiting for animals to drink, seeking shade, or marking a safe arrival. The panels are, in that sense, timestamps of lived routine.

Did You Know?

One of the sites west of the ancient wells of Bi’r Hima was so densely illustrated that a member of Harry St. John Philby’s 1952 expedition was able to copy 250 images without moving from his position.

Closing Thoughts

Ḥimā is not a single story. It's a shelf of them. On these rocks, Saudi Arabia remembers itself: the routes that stitched regions together, the water that made community possible, the letters that carried language into history. To stand at Bir Ḥimā is to feel how present the past can be. The library is open, and its pages still catch the light.

Curious for More Cultural Gems Like This?

Explore Saudi traditions, places, and living heritage across the Kingdom at Saudi Culture.