In Saudi Arabia, mosque architecture does not follow one “national” shape. It follows the land. A prayer space in a mountain village cannot be built like one on the Red Sea coast, and a neighborhood mosque does not carry the same needs as a Friday mosque welcoming large crowds. Across the Kingdom, mosques reflect climate, local materials, and the rhythms of community life, while holding steady to the same sacred direction.

Why Mosque Architecture in Saudi Arabia Looks So Different

Saudi Arabia’s historical mosques were shaped by practical questions long before modern cooling and concrete. What is available to build with? How does a wall resist heat, humidity, or seasonal rain? How can light enter without sacrificing privacy?

Historic mosques in Saudi Arabia are often known for practical, straightforward construction and a generally restrained approach to decoration. At the same time, the Kingdom’s mosque architecture is far from uniform. It can be understood through distinct regional traditions shaped by geography, climate, local culture, and building methods such as Hijazi and Red Sea styles, Tihama and the Sarawat Mountains, the southern desert and Aseer, the Najdi heartland, Al-Ahsa, the Arabian Gulf coast, and northern regions.

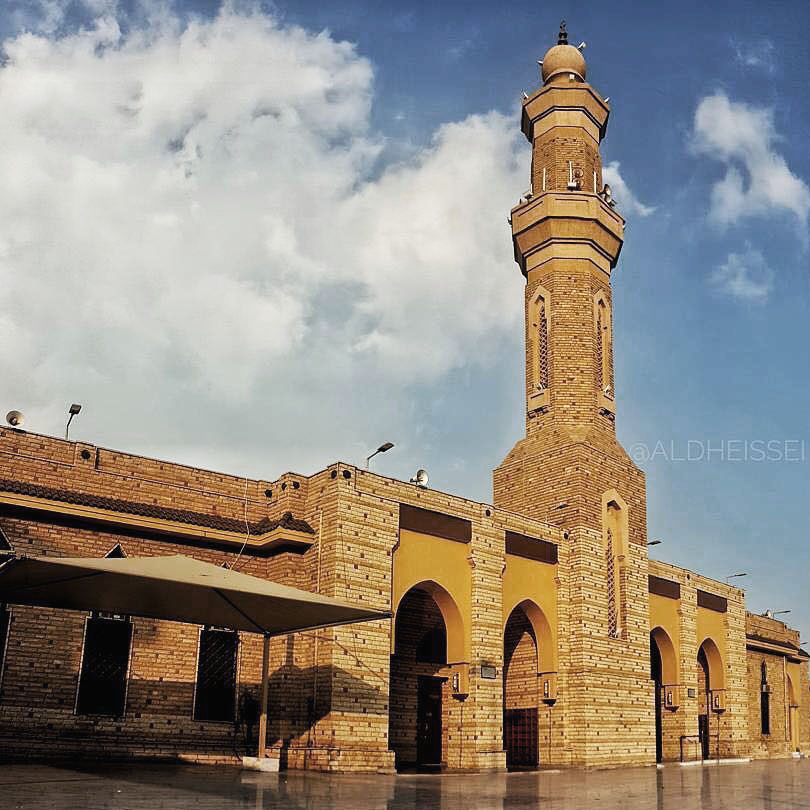

1) Najdi Mosques: Built from the Earth, Designed for Endurance

In central Arabia, Najdi mosque architecture is closely tied to earth-based construction, especially clay and adobe techniques that suit the region’s environment. This tradition is strongly associated with areas such as Riyadh, Al-Qassim, and Hail, where builders have historically worked with clay, and in some places combined it with local stone.

This material logic shapes the design. Thick earthen walls help moderate heat, leading to mosques that feel calm and grounded: solid, protective forms; carefully sized openings; and spaces that favor shade and privacy. While details differ from town to town, Najdi mosques are often best understood as architecture shaped by climate, local materials, and practical building knowledge passed through generations.

2) Hijazi and Red Sea Influences: Rawasheen, Light, and Coastal Craft

Along the western region, Hijazi mosque architecture is often recognized for its refined woodcraft, especially rawasheen and the latticework elements associated with mashrabiya. Traditionally, this design was not only decorative. The patterned openings helped guide airflow, and when water was placed nearby, it could support a cooling effect through evaporation, creating a gentler indoor breeze.

Rawasheen also serve multiple daily needs at once: they bring in filtered light, improve ventilation, and protect privacy. In Makkah, these architectural solutions grew within a city shaped by constant movement of pilgrims, traders, and visitors, where different building skills and decorative influences met and blended over time.

3) Southern Saudi Styles: Stone, Timber, and Mountain Logic

In the south, mosque construction responds to terrain and weather that are very different from the central desert. In the Sarawat highlands, stone building traditions are common across mountain communities in places like Al-Baha, Taif, Aseer, and Jazan. In the Tihama lowlands, construction methods have historically varied, sometimes featuring multi-story stone structures, and in other settings relying on readily available natural materials such as branches and plant matter.

A strong historical example is Tabab Mosque in Tabab Village, commissioned in 1805. It is often cited as a standout model of southern provincial mosque design from that era, built mainly from stone and wood, and marked by multiple arches inside and out. These details are more than technical notes. They show how local builders expressed the same sacred purpose through forms that matched mountain materials, community scale, and regional craft.

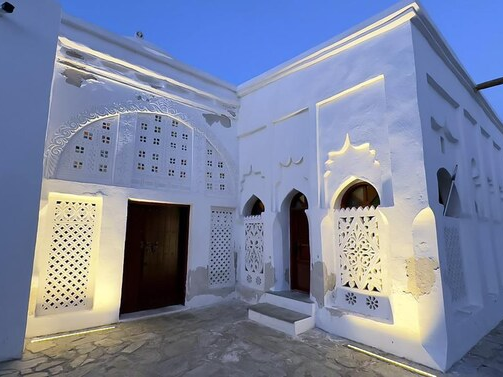

4) Farasan’s Al-Najdi Mosque: When Trade Routes Leave a Signature

Sometimes, a mosque becomes a record of movement of merchants, craftsmen, and materials carried across the sea. On Farasan Island, Al-Najdi Mosque is often described as a rectangular complex with an open courtyard and multiple entrances. Its thick stone walls are finished in a way that gives a gypsum-like appearance. Construction is commonly dated to 1916, and it is said to have taken around thirteen years, with decorative panels, paintings, and engravings brought from India, and skilled builders from Yemen involved in the work.

Inside, the mosque is especially remembered for its rich ornament, decorated domes, carved geometric plasterwork, and an Andalusian-inspired decorative touch around features like the mihrab and pulpit, details that make it feel both deeply local and unmistakably connected to wider artistic worlds.

5) The Two Holy Mosques: Architecture Designed for the World

Al-Masjid Al-Haram in Makkah and Al-Masjid An-Nabawi in Madinah are not only sacred landmarks. They are among the most demanding architectural environments on earth built to receive people from every country, language, and age group, in numbers that change by season, by hour, and even by minute.

This global reality shaped the architecture in very specific ways. Space is not treated as an aesthetic luxury, but a form of care. Vast prayer areas, open courtyards, clear pathways, and layered entrances are essential because movement itself becomes part of the worship experience. The architecture must protect worshippers from heat, reduce congestion, support accessibility, and preserve visibility and orientation, so people can remain spiritually focused even within enormous crowds.

The western region’s identity also matters here. Makkah and Madinah are not isolated cities; they sit within a Hijazi landscape historically shaped by arrival and hospitality. The built environment reflects this role, where design decisions are constantly tested by the needs of visitors who may be navigating the space for the first time, yet must feel guided, safe, and welcomed.

Modern Saudi Mosques: Comfort Engineering with Sacred Orientation

Modern mosque design still works with the same fundamentals while solving today’s realities: dense cities, higher visitor flows, and environmental comfort. One of the most recognizable contemporary interventions sits in the courtyards of the Prophet’s Mosque: the large, convertible shading umbrellas. A technical project description by SL-Rasch explains that the shading system provides sheltered space for large numbers of people, and that the umbrellas are arranged in groups, with gaps along the main axis enabling unobstructed views of the mosque and minarets to support orientation.

This is modern mosque architecture in a Saudi context: engineering in service of worship, and infrastructure designed to protect the spiritual “reading” of place, so the mosque remains visually and emotionally central.

Futuristic Forms: KAFD Grand Mosque and the Desert Rose

Saudi mosque design is also moving confidently into future-facing geometry without severing cultural memory. The KAFD Grand Mosque in Riyadh offers a powerful example. The official KAFD description says the mosque was inspired by the desert rose native to the Arabian Peninsula, forming a unique geometric structure with a column-free roof. It also notes two sculpted 60-meter minarets and an interior language connected to triangular design elements.

The mosque received major recognition, including being a winner in the Abdullatif Al Fozan Award for Mosque Architecture (2021).

Al Fozan Award: Setting the Global Standard for Mosques

When people say “setting the standard,” they usually mean more than taste. They mean clear criteria, documentation, and a global conversation about what mosque architecture should achieve. Established in 2011, the Abdullatif Al Fozan Award for Mosque Architecture describes itself as a triennial prize judged by an international jury, created to advance contemporary mosque design while honoring the spirit of tradition, supported by a curated database and categories such as Central, Jumaa, and Local, alongside special recognition for innovative ideas.

In practical terms, it helps shape design culture by spotlighting strong models and pushing the discussion beyond surface beauty, toward how a mosque truly serves worshippers, neighborhoods, and cities.

One Qibla, Many Architectures

Across Saudi Arabia, mosques carry one direction but many architectural dialects. Clay and volcanic stone in the center. Crafted rawasheen and mashrabiyas on the western coast. Stone-and-wood arches in the south. Imported panels and Andalusian motifs on an island shaped by trade. And in Riyadh’s new districts, a desert rose becomes geometry, proving that modern design can still speak Saudi.

In the Kingdom, mosque architecture does not simply change with time. It gathers meaning layer by layer while staying faithful to its purpose.

Curious for More Cultural Gems Like This?

Subscribe to Saudi Cultures for deep dives into traditions, regional stories, and voices from across the Kingdom.